Developers Really Hate Scrum? No!

Increasingly, I encounter developers who don’t seem to enjoy using the Scrum Framework to deliver software, and this is a cause for concern because I have fond memories from my days as a developer working on a Scrum Team. I relished the collaborative atmosphere within the team, where everyone supported each other in development, testing, deployment, and held a shared sense of accountability.

However, nowadays, I hear developers express their discontent with Scrum for various reasons, including:

- The Scrum Framework is perceived as primarily a task management framework.

- Concerns about spending too much time in meetings at the expense of productive work.

- Frustration with estimation, as it’s often considered inaccurate, leading to blame from managers for missed deliveries.

- Difficulty focusing on the sprint backlog due to business-as-usual (BAU) or support work.

- Questioning the value of the Daily Scrum, preferring to send daily updates via email. These concerns are valid, and I believe they stem from experiences with Scrum that involve inexperienced or ineffective Scrum Masters. In this post, I aim to address these assumptions and misinformation related to what I call “Mechanical Scrum.”

Mechanical Scrum is a term often used to describe teams that go through the motions of Scrum without a deep understanding of its principles.

Scrum, as a framework, is well-suited for delivering valuable products in complex domains, even when there are many “unknown unknowns” in product delivery. Scrum enables incremental and iterative value delivery. To make this happen, the team must become self-managing. Scrum encourages setting goals and promotes transparency by inspecting progress toward those goals. These goals are collaboratively defined with stakeholders, and developers, as part of the Scrum Team, are empowered to determine how to achieve them, free from external interference.

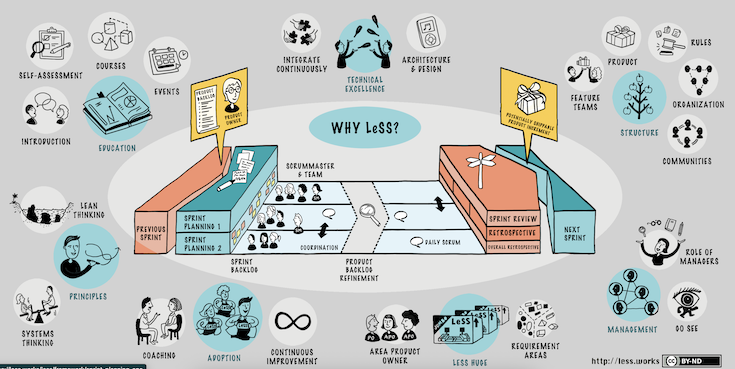

Scrum defines four key events that facilitate Transparency, Inspection, and Adaptation:

Sprint Planning: The Scrum Team sets the Sprint Goal, and developers select backlog items they believe will help achieve it.

Daily Scrum: A brief daily event where the team plans the next 24 hours and inspects progress toward the Sprint Goal.

Sprint Review: Towards the end of the Sprint, developers meet with stakeholders to showcase outcomes, gather feedback, and discuss objectives for the next Sprint.

Sprint Retrospective: A meeting to inspect the team, tools, and processes, ensuring ongoing value delivery.

These events are time-boxed, but in my experience, no Scrum Team has spent more than 5 hours and 30 minutes on these events in a two-week Sprint (80 hours). If developers feel that these events are taking too long, they can discuss this in a Sprint Retrospective and potentially adjust the time spent, as long as it doesn’t hinder value delivery.

Estimation has been a topic of debate in many teams I’ve worked with, but it’s important to note that estimation is not a core part of the Scrum Framework; it’s a practice often added by practitioners. There are alternatives, such as “no estimates,” where the team measures work done by counting completed Product Backlog Items (PBIs). This approach helps plan for subsequent Sprints. Flow metrics are another viable alternative to traditional estimation.

Difficulty in focusing on Sprint work due to BAU/Support work is valid feedback that should be discussed within the team. There are several strategies to address this, such as adjusting Sprint commitments based on expected BAU/Support work or tracking the time spent on such work to make informed decisions on reducing it over time.

The Daily Scrum is not merely an update meeting; it’s an event to plan the next 24 hours collaboratively. Developers may request to send updates via email if the purpose of the Daily Scrum is misunderstood. Typically, during the Daily Scrum, developers discuss what they need to work on collectively to move one day closer to the Sprint Goal. In cases where developers work on multiple projects or products within the same Scrum team, the Daily Scrum may have limited utility.

In conclusion, the frustrations expressed by developers often stem from the unfounded assumption that they can’t address their own challenges. These issues, as described above, are topics that can be discussed in retrospectives, enabling developers to adjust their ways of working. Self-management lies at the heart of Scrum, and people tend to complain when they feel powerless in their own situations.

To learn more about Professional Scrum, join me in one of our scheduled Professional Scrum Master public classes.